Point 1966 via Freehold Creek, Twizel

Point 1966 is the high point of a very long hike I did in the mountains west of Lake Ōhau. The trailhead is near Lake Ōhau Alpine Village, around 30 minutes from Twizel and from Ōmarama in the Mackenzie Basin region of Canterbury, South Island.

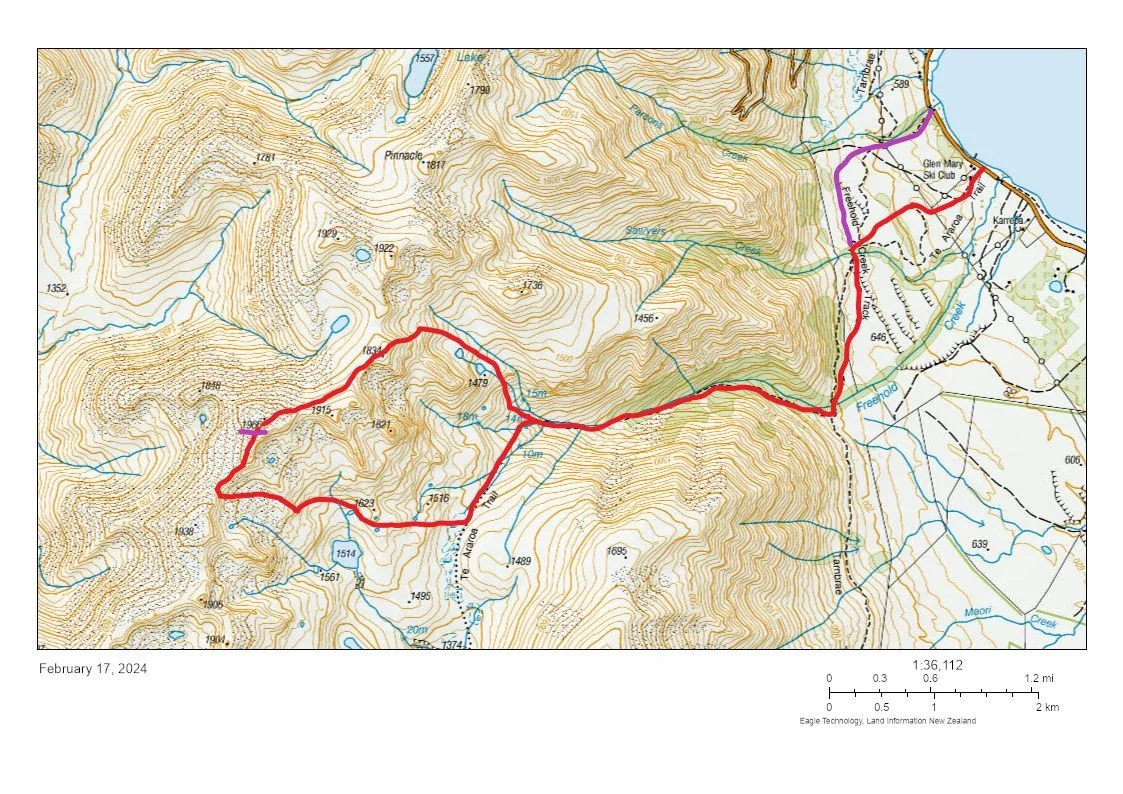

I started at Glen Mary ski club on Sawyer’s Creek track (part of the Te Araroa trail), which merged with the Freehold Creek track; next I headed through tussock, roughly following the beginning of the route to Lake Dumb-bell; then I ascended to the rocky tops featuring Points 1834 and 1966, before descending into a basin below Point 1966; and finally I regained the Te Araroa trail, which took me back the way I had come, passing back over Freehold Creek track and Sawyer’s Creek track.

It’s not clear from the topomap whether Point 1966 is in the Ōhau Range, or in an an unnamed chain between the Ōhau Range to the southeast and the Barrier Range to the west. That doesn’t matter, but something else does. Don’t confuse the Ōhau Range with the Ben Ōhau Range, which is on the far (east) side of Lake Ōhau. (Click here for my hike in that range.)

Time

Including breaks, the entire hike took me a little under 11 hours. I reached Point 1966 in about 5 hours 40 minutes, including breaks. It is underlined in purple in the topomap screenshot.

Access

The trailheads. See description under ‘Access’.

Screenshots of the NZ topographic map are licensed as CC BY 4.0 by Toitū Te Whenua Land Information New Zealand (LINZ).

There are two different tracks leading to the foot of the valley surrounding Freehold Creek, thus there are two possible trailheads at which to park. First, notice the three creeks on the topomap, each flowing down from the west toward Lake Ōhau.

Furthest north is Parson’s Creek. The Parson’s Creek to Freehold Creek Track - which is labeled with the shorter name Freehold Creek Track on the topomap - starts about where Parson’s Creek flows into the lake. There is a DOC parking area.

In the middle is Sawyer’s Creek. Glen Mary ski club is based a little north of where it flows into the lake. Non-club members can’t park in their compound, but they are allowed to park beside the road and follow the Sawyer’s Creek track (Te Araroa trail) through the club compound. This was my starting point.

Furthest south is Freehold Creek. This is the creek beside the ascent route, but there is no trailhead near where it flows into the lake.

To make things more confusing, these tracks intersect and perhaps overlap the Tarnbrae mountain biking track. I saw several cyclists, but no hikers.

Route

The purple track at right is from the alternative trailhead at Parson’s Creek. The purple line near left indicates the high point, 1966. I hiked the loop counter-clockwise.

Screenshots of the NZ topographic map are licensed as CC BY 4.0 by Toitū Te Whenua Land Information New Zealand (LINZ).

From Glen Mary ski club, I started on the 4WD Te Araroa trail, but soon spotted an impact track that took a more direct route toward the bridge over Sawyer’s Creek. There were some small cairns alongside the impact track.

The impact track, Freehold Creek track (from the Parson’s Creek trailhead), and Sawyer’s Creek track/Te Araroa trail (from the Glen Mary ski club trailhead), all merge near the bridge over Sawyer’s Creek. From here, the track was in and out of forest until it reached Freehold Creek. Once there, I turned west and ascended the easy forest track up the valley, on the true right of Freehold Creek. I don’t think the cyclists use this track.

At the top of the forest, the track continues uphill, marked by poles with both yellow and orange plastic. Further up, there is a DOC sign marking the diverging routes: left/southwest to the East Ahuriri valley (on the Te Araroa trail), following orange poles, or right/northwest to Lake Dumbell, following yellow poles.

I turned right, but soon after that, I departed the poled route soon to put on sunscreen in the shade of a large rock. After that, instead of immediately returning to the Lake Dumbell route, I ascended directly up the rocks and tussock toward the tarn near Point 1479 for around 150 meters. This was a mistake. In particular, I don’t like the tussock in this area, which is more greener, smaller, and more slippery than the tawny Otago snow tussock with which I’m most familiar.

As I approached the Point 1479 tarn, I rejoined the poled route, but left it again for a direct ascent to Point 1834, on a steep slope of loose rock. This was the most fun part of my hike, and I would do it again, but it’s probably easier to ascend less steeply to the saddle north of Point 1834. My steep ascent to Point 1834 didn’t have any meaningfully exposed portions, because so much of it is loose rock and so little of it is solid outcropping.

From Point 1834, I looked north at the saddle between Point 1929 (left/west) and 1922 (right/east). Between them is one of at least two routes to Lake Dumb-bell, not necessarily the safest or easiest one (I haven’t researched it).

Then I turned to face southwest, and began a straightforward walk to Point 1966, which has no important features. It would be quite hard to do it in the opposite direction on a windy day, however, because of the loose rocks underfoot. To my surprise, the only bird soaring above me as I walked along the ridge was a gull, not a kea. Maybe I should ask for a refund of my entry price?

Continuing southwest from Point 1966, I descended to the saddle between Point 1966 and Point 1938, then took a steep descent east, on an undifferentiated slope of loose rocks, into the basin.

Once in the basin, I maneuvered northeast over gentle hills of loose rock, and then through tussock at lower elevations, until I joined the Te Araroa trail heading north toward Freehold Creek. As you would guess from the marshland indicated on the topomap screenshot, I passed through large expanses of moss and mud shortly before reaching the trail, so this route might be challenging in wet conditions. Luckily I had a sunny day and all the mud exposed to the sun was dry.

To my surprise, the most painstaking part of the hike was descending the Te Araroa trail to the top of the Freehold Creek forest. How, you ask, could this be worse than descending steeply on loose rocks or slippery green tussock? It’s because dense tussock beside the track sometimes hides the track from view, making it almost impossible to see holes. I stepped into a hole roughly 40cm deep at one point, and into a mud puddle around 15cm deep later on. The tussock shades the mud puddles, preserving them from the sun’s drying effect.

Luckily, I was wearing my OR crocodile gaiters when I stepped in the mud puddle. I highly recommend them for this hike.

Hiking the loop counter-clockwise was a good idea:

The majority of the time, it was probably easier to see what I was aiming at, due to the topography.

Had the prevailing northwesterly wind been strong, it would have been at my back as I walked from Point 1834 to Point 1966 to the saddle below Point 1966.

Turning around at Point 1834 instead of continuing to Point 1966 would save a lot of time for someone who is moving slowly. But the reverse is not true. It’s probably a bit faster to return from Point 1966 via the saddle north of Point 1834, and a bit slower to turn around and return by the ascent route. (Unless there is strong wind.)

If 1 is an easy track, and 4 is using hands and feet on exposed rocks, this route is a 3 at worst. Looking at photos below, you might be surprised that I don’t rate any of the ascent to Point 1834 a 4. There simply wasn’t much exposure where I walked, although there would have been with a more reckless route over certain outcroppings.

Hunting

The entire route is in a hunting area. Hunters are forbidden to “discharge firearms near tracks, huts, campsites, road-ends or any other public place.” I have hiked in more than 30 hunting areas, and only passed hunters twice - this wasn’t one of those hikes.

Here is the DOC topomap with all hunting areas visible.

Pages about overlapping hikes, mostly heading for Lake Dumb-bell

https://s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/au.mapspast.org.nz/shared/20211213-Ahuriri-Ohau-TripReport.pdf (a circuit of similar shape to mine, but much longer)

https://ssdavies.net/2016/02/18/freehold-creek-towards-dumbell-lake/ (day-trip almost to Point 1834; GPX)

https://westcoastwayfarer.com/hiking/ohau-range-new-zealand/

https://ctc.org.nz/index.php/trip-reports?goto=tripreports%2F1032

https://otmc.co.nz/files/bulletin_pdf_files/2011/2011-02.pdf (pages 9-11)

Nearby hikes

Double Peak, Lindis Pass

Sealy Tarns, Mt Cook village

Local history

On his inland journey southward, Rakaihautu used his famous kō (a tool similar to a spade) to dig the principal lakes of Te Wai Pounamu [South Island], including Ōhau. It is probable that the name “Ōhau” comes from one of the descendants of Rakaihautu, Hau.

This hike seen from elsewhere

June scene from around the Ōhau Downs area. Ben Ōhau at right. Mt Sutton center-left. Freehold Creek is probably the valley visible at left. If it is, then the Ōhau Range rises furthest left, with Ōhau Peak out of sight. Point 1966 is also out of sight.

Photo taken from the peak of Ben Ōhau.

Sawyer's Creek far right; Freehold Creek right. Directly above the Freehold Creek forest is a peak with a huge dark rock protrusion. Point 1834 is the top of this peak. Point 1966 is further back to the left, and appears lower.