How can we reduce risk in the mountains of Aotearoa New Zealand? An easy way is using the Mountain Safety Council’s all-in-one Plan My Walk website and app for notifications about weather and other hazards.

In case something goes wrong, you’ll want to have some sort of distress beacon, such as a personal locator beacon (PLB). They can be purchased or rented.

A Wilderness Magazine article: “Every year as many as 11 trampers and climbers die in the backcountry. How are they dying and how can you avoid it?” Falling and drowning are the two most common sorts of death.

This page covers how I think about various risks.

Sunburn

I have never skied or snowboarded, so I had never considered UV rays reflecting off of snow. Then came my early summer hike on Mt Fyffe and the ridge toward Gable Peak, near Kaikōura, Canterbury. That was the day that I learned how bad UV rays reflecting off snow are. Be careful!

Sunburn occurs surprisingly rapidly in NZ. Atmospheric researcher Richard McKenzie says UV radiation is 37% greater in NZ summer than at the corresponding latitude in the Northern Hemisphere summer. The breakdown:

7% due to the Earth's elliptical orbit,

20% due to cleaner Southern Hemisphere air, and

10% due to atmospheric circulation causing lower levels of ozone.

Then, altitude makes sunburn worse: "UV radiation increases 4% for every 300m increase in elevation.” Compare:

UV in Queenstown, at 300-400 meters, with

UV in a nearby ski field, The Remarkables, at 1600-2000 meters.

Those two graphs reflect NIWA UV and ozone forecasts, which you can find updated daily on the NIWA website and on apps like UV NZ.

The UV NZ app converts the UV index to (relatively) safe exposure times, which vary by skin type. The default is type 2 skin. Setting it to type 1 skin (paler skin) produces shorter burn times.

Snow reflects UV radiation very well - 80% of it. Hiking on snow, in summer, at high altitude seems like one of the riskiest activities for sunburn.

In summer you might want to prioritize hikes which are largely beneath a forest canopy. This means regions like the West Coast, Lewis Pass, Abel Tasman, Marlborough Sounds, Arthur’s Pass, and Fiordland on South Island; and most of North Island, except Tongariro and certain Wellington hikes.

Facing north-northwest. Rain coming from the northwest, seen from Mt Aicken, a mountain on the east side of Arthur’s Pass, Canterbury. My last photo before descending into the forest.

Wind and rain

New Zealand's weather systems mostly come from either the northwest or the northeast. The northeastern weather systems, including the cyclones, are mostly a threat to North Island. Rain and strong wind from the northwest are the main challenge for South Island hikers.

Lenticular clouds are a warning sign of an incoming northwester:

An infallible weather sign and one that must be heeded when “outback” is the formation of “hogsbacks”—peculiar shaped zeppelin-like clouds that develop out of a clear sky when the weather seems set for weeks. Their appearance always presages a nor'west storm and usually means an end to climbing for several days.

C.H. Fortune, Railways Magazine, 1933

No, I don’t remember why I was reading a 1933 magazine, but at least we’ve learned that the word “outback” was once used for NZ as well as Australia. Anyway, for more contemporary coverage of the northwesterly wind, see New Zealand Geographic.

Facing south. Cloud blown uphill from the east/northeast, Te Atuaoparapara, Ruahine Range, Central Hawke’s Bay. It didn’t stop me from reaching the summit, but visibility was low.

Weather systems from both northwest and northeast can cause significant floods, which seem to kill people each year. Drowning actually gained a reputation as "the New Zealand death" in the 19th century British Empire. (It’s sometimes said that we have the early settlers’ justified fear of drowning to thank for the present location of some hiking trails, because the settlers were consciously looking to travel by less flood-prone routes.)

The risk of floods is a small part of the reason why, when I rent cars, I keep my Quell window-hammer/seatbelt-cutter at hand. Rental cars rarely have anything of the sort. (The tool is also a flashlight/torch and flashing emergency beacon.) That said, I think accidentally driving off the side of a road with no guardrails is a much bigger risk than driving into a flood. Escaping from a car after that happens is my main reason for having a window-hammer handy.

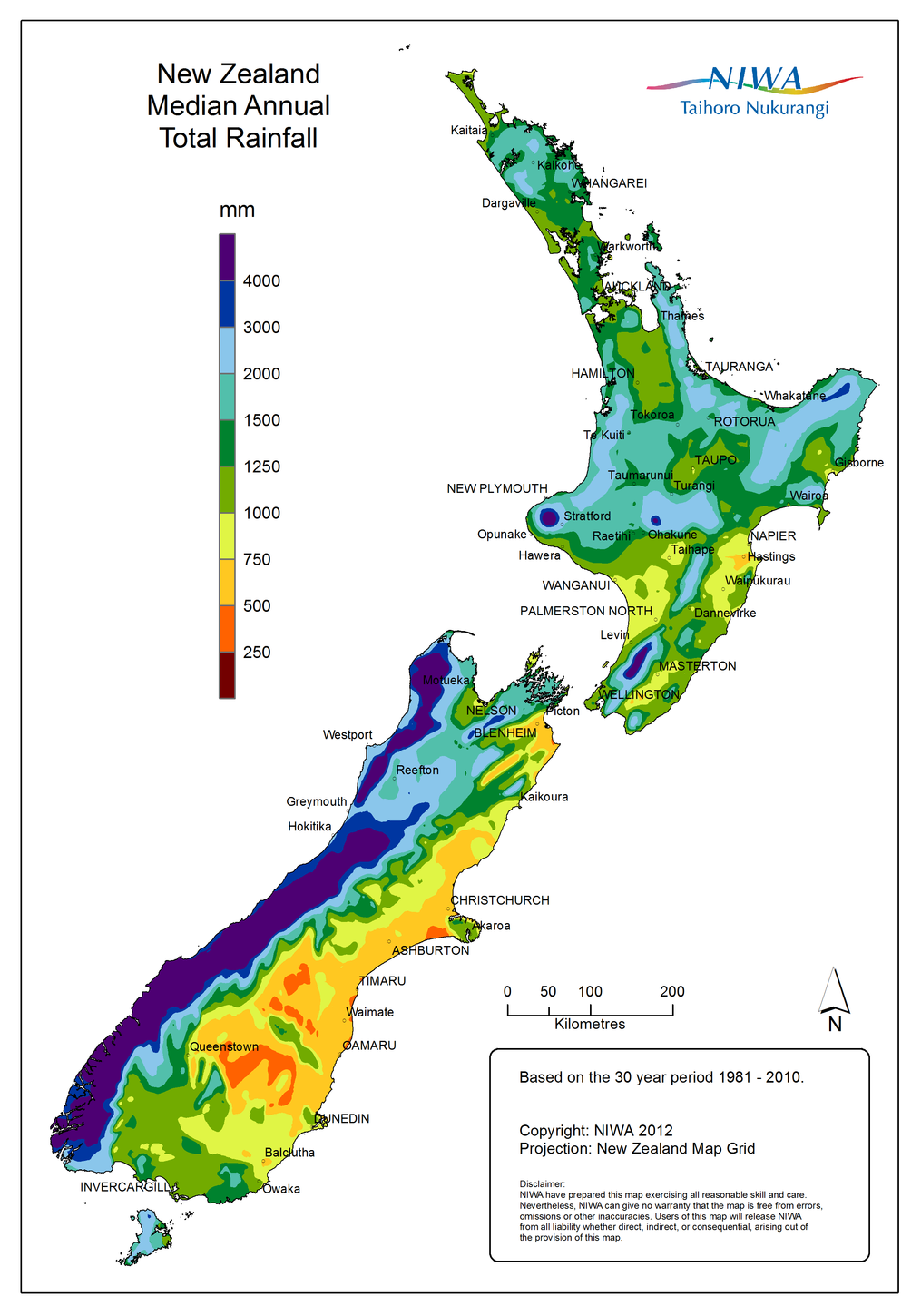

Copyright NIWA, used with permission. https://niwa.co.nz/climate/national-and-regional-climate-maps/national. I like to hike where the colors resemble pizza and pasta. But not where the colors resemble squid-ink pasta.

NIWA’s rainfall tables help me schedule hiking trips in less rainy regions during less rainy months. (Here is a simplified overview.) Over recent decades in most of South Island,

December tends to be particularly rainy, e.g. Arthur’s Pass, Canterbury averaged 508 mL.

I have heard that late December tends to be the least rainy part of the month, which sounds good for Christmas-New Year’s travelers. But I can't find data.

February tends to be particularly dry, e.g. Arthur’s Pass averaged 267 mL.

I rarely hike on the particularly rainy (and sandfly-infested) West Coast of South Island. The rain shadow effect means that further east on South Island is generally less rainy.

For example, Canterbury hikers who find themselves rained out in Arthur's Pass can drive 20-60 minutes to the southeast, to

northern Craigieburn Forest Park

Castle Hill area:

Kura Tawhiti (Castle Hill rocks)

Korowai-Torlesse Tussocklands Park

NIWA national parks forecasts are useful for hikers because they highlight risks, such as wind speed above certain thresholds. The government also sponsors human-interpreted national parks forecasts from MetService. (Why both? Read this.)

Some NZ hikers consult the Norwegian Meteorological Institute (yr.no) forecasts as well.

Heavy rainfall increases the risk of landslides/slips.

Facing west. Kea demonstrating how to ride a strong northwesterly wind. Mt Lyndon, near Castle Hill, Canterbury. Left: Red Hill. Right: Craigieburn Range.

Snow and avalanches

Edward has written a lot of advice about hiking in the snow here: https://hikingscenery.com/winter-tramping-in-new-zealand/.

Two types of avalanche advisory, to use together:

DOC rates underlying terrain on the Avalanche Terrain Exposure Scale; this is independent of the presence of snow

Mountain Safety Council posts an Avalanche Advisory for 12 alpine regions based on current weather/snow conditions. (Here is the user guide.)

I’ve learned about avalanches by completing the Mountain Safety Council’s recommended online training module (allow one hour) and this US-produced Know Before You Go video (15 minutes). The Mountain Safety Council also posts their own YouTube videos about:

The Wānaka DOC warned me about slab avalanches on the approach to the famous Roy’s Peak lookout. I’m guessing that this is some of the terrain onto which avalanches flow from the left.

There are a lot of providers of snow skills courses with avalanche safety components.

I won’t try to paraphrase the above texts’ and videos’ important advice, but I will quote Wilderlife on one thing they don’t cover:

Rifles have almost nothing in common with ice-axes and cannot be used as such.

The more general principle here is, if you don’t have an actual ice axe, don’t do hikes requiring an ice axe. Cf. Edward’s description of using an ice axe on Barrier Knob, Fiordland.

Webcams can give a good idea of whether snow is present on certain hiking trails, even though that isn’t the purpose of the webcams. For example, webcams here show the famous Roy's Peak near Wānaka.

There are also highway webcams, useful for checking snow levels on roadside hikes, or on the road. The NZTA website’s Journeys tool shows road closures due to snow. Lindis Pass below is one of the more frequently closed roads during snowstorms.

Lindis Pass sometimes closes with snowfall. It connects Central Otago and the Queenstown Lakes region (to the left) with the Mackenzie Basin (Canterbury). Seen from Double Peak.

MetService ski field snow reports sound potentially useful for winter hikers.

Crossing rivers and streams

A lot of NZ hikes involve one or more stream crossings, and a moderate number involve one or more proper river crossings. The Federated Mountain Clubs provide guidance in their magazine, Wilderlife. A few things I didn’t know:

Do not wade a river if:… The crossing point takes you to the outer side of a curve in the river, especially if it is a sharp bend as there is likely to be a deep channel there…

[O]nce the river level rises to catch your pack, the force from the current will increase dramatically and at the same time your feet will have less grip as you start to float…

Always keep your boots on. If you are expecting prolonged snow travel afterwards, remove you [sic] dry socks before entering the water. Once crossed, replace your socks, put your feet inside plastic bags, and then back into the boots.

I’ve never tried to cross a stream higher than my Outdoor Research Crocodile gaiters. I just plan easier hikes!

Water levels tend to be higher during, and for a few days after, rainfall. For example, the amount of recent rainfall determines whether the Buckler Burn - separating Mt McIntosh/Black Peak and Mt Judah/Heather Jock Loop/Mt Alaska near Glenorchy, Otago - can be crossed safely.

Falls

Falling has been the main cause of death for climbers and trampers this century. Part of this is basic physics:

When planting a foot during a descent, there is less opportunity to test the traction of the placement before the full weight of the body is committed to the step. When ascending, the weight remains on the downhill leg until the foot placement has been made, and even if a loss of traction occurs it is more recoverable because the foot that slips has little weight behind it. Also, if the downhill foot slips during a descent, the direction of travel is downhill, meaning that there is more momentum to overcome in terms of recovery.

—New Zealand Search and Rescue, Feb 2018

Footwear plays a role:

I’ve seen a lot of inappropriate footwear [on dead hikers]. You need proper footwear for conditions where a fall could be fatal and that means having a boot with a stiffer sole. A stiff sole gives far more support as it will grip on tussock or a piece of scree, whereas a less stiff sole is more likely to slip, and away you go.

—David Crerar, longtime South Island coroner, quoted in Wilderness Magazine

Insects, spiders, and snakes

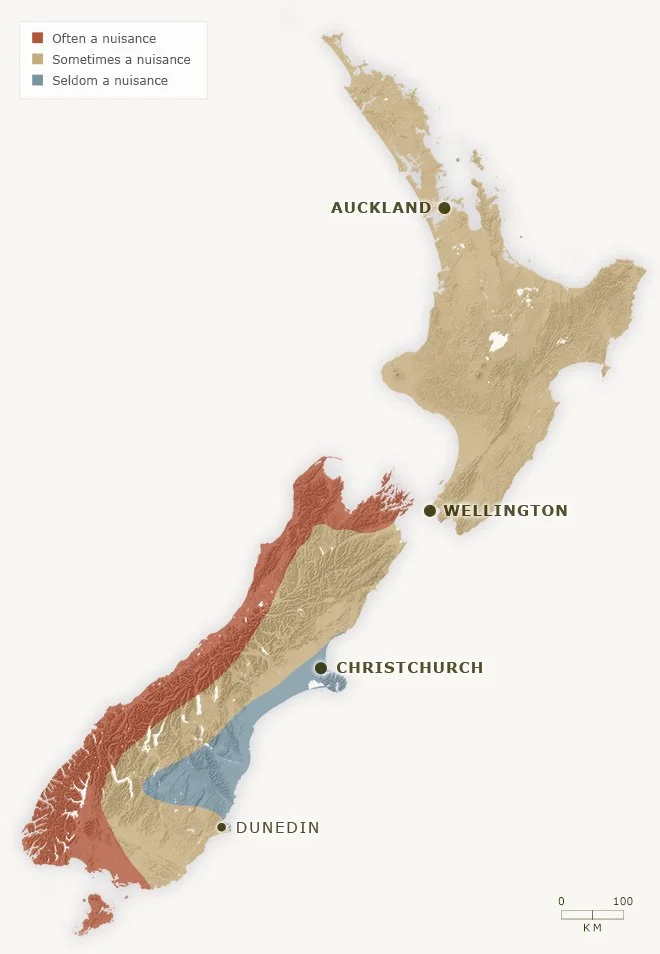

This map offers a rough guide to nationwide sandfly risk. Fiordland is the westernmost red area, with visible fjords.

Copyright Te Ara (https://teara.govt.nz/en/map/14737/sandfly-nuisance-map), used with permission. Te Ara’s map is based on info in Marjorie Orr’s book Those sandflies.

There are no snakes! NZ 1, Australia 0.

The Ministry of Health (Te Whatu Ora) lists a few species of venomous spiders on their website: the katipō, redback and white-tailed spiders. I had never heard of them before seeing that webpage. Their venom is generally not as harmful as the worst spiders elsewhere. NZ 2, Australia 0.

There are a few species of biting or stinging insects. As far as I know, none carry any diseases that affect humans. NZ 3, Australia 0.

The main nuisance insect in NZ is the black fly, which is called the ‘sandfly’ in NZ. Their bites are itchy and they swarm. See map. Fiordland and nearby are often said to be the worst places:

The Maori claimed that when Hine-nui-te-po (the goddess of the underworld) saw the fiords, she deemed them too beautiful to be modified by man. As a deterrent, she released a liberal dose of sandflies. Her ploy worked. Most Maori restricted their visits to the area to occasional hunting, fishing and greenstone-gathering trips. Even today, the human population density of Fiordland remains virtually zero.

Claudia Babirat, New Zealand Geographic

Sandflies congregate near water, including beaches, especially around dawn and dusk. Hiking uphill quickly is a decent way to get away from them. When they land on you:

The good folk of the South Island’s West Coast have a way of distinguishing a tourist from a local, even from a great distance. A local, they will tell you, is a “brusher”, while visitors are “slappers”.

Babirat, New Zealand Geographic

Okarito citronella sandfly repellent, which can be purchased in Department of Conservation (DOC) offices, seems to discourage sandflies. The roll-on version tends to leak, so I keep it in a sealed plastic bag. If I were worried about insect-borne diseases, I would use the more effective DEET (the particularly smelly one) or Picaridin instead.

We are advised to wait 20 minutes between putting on sunscreen and putting on insect repellent.

I have seen some mosquitoes in Auckland. I don’t recall seeing any while hiking. I have seen stinging bees in cities - indeed, been stung by one at Auckland Zoo - and at rural apiaries.

I have heard complaints about how common wasps are in Kahurangi National Park, in the Tasman and West Coast Districts. I visited the Tasman part of the park in November, and didn’t see any wasps.

Hazardous plants (“the flora is lava”)

Speargrass, lurking inside of a harmless bush.

Watch out for two sharp plants:

matagouri thornbushes (a.k.a. wild Irishman)

taramea/speargrass (a.k.a. wild Spaniard) - pictured

Speargrass might blind a person who fell into it face first. Be careful or be Oedipus.

As in many countries, there are various poisonous or irritating plants. The Ministry of Health (Te Whatu Ora) only mentions 3 species of stinging nettles in the bites and stings section of their website, alongside insect bites and stings. This leads me to assume that the other plants are less significant. Alternatively, the website is negligent. I don’t think I’ve encountered an irritating plant in the NZ bush.

To reduce risk from both sunburn and speargrass, I almost constantly wear lightweight gloves while hiking. Unfortunately, speargrass is still pretty sharp through lightweight gloves.

Outdoor Research Crocodile gaiters also help. Going hiking while wearing shorts but not gaiters is the worst choice:

Fortunately we had a 14-year-old with us, who insisted he was absolutely fine wearing shorts and charged ahead, his yelps of pain providing an effective [speargrass] warning system for the rest of us.

-Vicky Virtue, NZ Herald

Hunting

Hunting is a fairly popular rural pastime. As shown by the DOC.govt.nz topomap, there is substantial overlap between hunting areas and hiking areas.

Hunters are forbidden to “discharge firearms near tracks, huts, campsites, road-ends or any other public place.” Hunters very rarely kill trampers.

Some advice from GJ Coop:

avoid tramping pre-dawn or post-dusk

noise is good, well, non-deer-like noise, clanking of walking sticks, etc

don’t dress in deer-like colours — brown, red, black. The most distinctive colour is United Nations blue so if you are buying a raincoat, pack, hat etc, at least think about the colour

He doesn’t mention goat-hunting. I would additionally avoid burnt orange and gray for this reason.

I’ve only passed hunters in two places - one with a crossbow near Sugarloaf Pass (Glenorchy, Otago), and two with rifles on Mt Oxford (next to the Canterbury Plains).

Earthquakes, volcanoes, and tsunamis

Like other places along the Pacific Ring of Fire, New Zealand is prone to earthquakes and has some active volcanoes. Downloading the government's free GeoNet Quake app is a good way to get notifications.

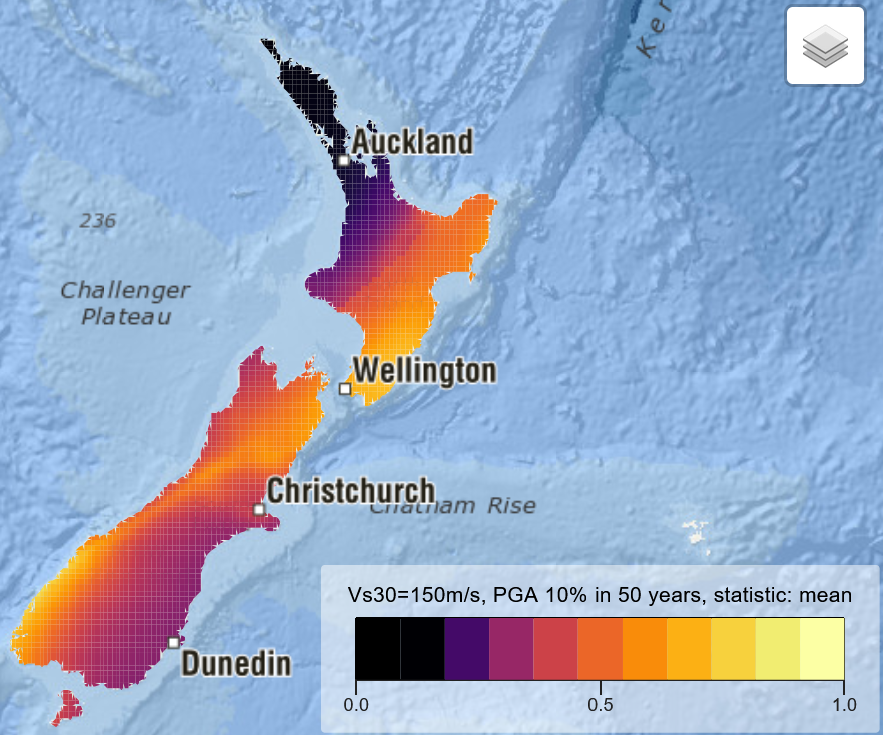

National Seismic Hazard Map, from https://nshm.gns.cri.nz/HazardMaps. Copyright GNS Science, used with permission. Brighter means higher risk.

Earthquake risk varies by region - see the National Seismic Hazard Model map, screenshot at right.

The map shows that Northland and Auckland have relatively low earthquake risk, which is interesting, because Auckland is the only city on an active volcanic field. (My Auckland photos include some of the city’s newest volcano, Rangitoto Island.)

GeoNet ranks volcanoes by alert level. When I hiked to Dome Summit on Mt Ruapehu, there was a warning to stay away from an exclusion zone around the alluring blue crater lake. At higher alert levels, the warning changes. It becomes a warning to stay away from the summit area entirely.

The longest South Island fault is the Alpine Fault. Journalist Lois Williams summarizes its status:

Core samples from West Coast lake beds in recent years show the giant fault along the spine of Te Wai Pounamu [South Island] has ruptured with remarkable regularity every 260 to 300 years. The last event was in 1717, making the next big one well overdue.

The present mayor of Auckland would like to remind you that his city’s rival, Wellington, is also expected to have a very intense earthquake at some point. An 1855 earthquake, with an epicenter a little to the east of Wellington, seems to have been New Zealand’s strongest recorded quake.

Tsunamis could hit anywhere along the coast. Zoom in on this map to see where the tsunami evacuation zones are. If you feel an earthquake which is either long or strong, leave the evacuation zone immediately - that’s why they call it an evacuation zone. Don’t wait for a tsunami warning.

Other

Orange usually indicates the route for hikers, while blue, pink, and other colors indicate something else, such as trap lines for invasive species. However, I have also seen blue poles and yellow poles for hikers.

DOC advises against hiking above the bushline when visibility is low.

Wildfire risk is particularly high during El Niño summers in Marlborough, Canterbury, and Otago. Once I saw smoke from a large fire rising over the Port Hills of Christchurch, on which I had been hiking two weeks earlier.

Hiking tracks commonly pass through former mining areas in e.g. Central Otago and the Queenstown Lakes Region. It is best not to step off the track when the ground is hidden by snow or vegetation, because there could be a mine shaft or rusting equipment. A DOC employee warned me about this.

In karst environments, like Mt Arthur in the Tasman District, it is best not to step off the track, because of sinkholes.

X (Twitter) accounts to follow:

disasters: @NZcivildefence

preparation: @NZGetReady

On being cold at high altitudes:

If you get cold walking up a hill when your body is at maximum thermal output, then you will be much colder on the descent. Turn around, get lower and warmer. If you get cold waiting for someone to catch up, then walk back towards them. It will keep you warm and help the other person – who may well be colder and more tired.

-Johnny Mulheron, ‘A Preventable Tragedy in the Young Valley’

Non-blog pages, like this one, don’t have comments sections, unfortunately. If I’ve made a mistake, please email me or post in any blog page’s comments section! Thank you.